Your Eldercare Compass

Helpful tips for family caregivers

July/August 2024

Our natural response when a loved one is sad is to want to “fix” it. Well intended as it is, research is showing this is not as constructive as learning to listen well. In our middle article we look at what you can do if you are concerned the hospital is releasing your relative before you feel it’s safe for them to be at home. Last, we follow up on our earlier article about the consequences of chronic inflammation. This month we look at the signs and symptoms and what can be done to diagnose the problem.

Listening when a loved one is sad

When we are sad, often the best medicine is to talk with someone. If you are the person listening, you may find it challenging to witness your loved one’s sadness as they struggle with the losses inherent to illness and aging.

When we are sad, often the best medicine is to talk with someone. If you are the person listening, you may find it challenging to witness your loved one’s sadness as they struggle with the losses inherent to illness and aging.

It’s natural to want to “fix” their emotional pain and make it go away. A common reflex is to suggest they “look on the bright side,” or reassure them that “everything will be okay.” Or jump in and help them by problem solving. While these responses may have their place, research shows that when done prematurely, such “helpful” strategies often backfire. The person you care for may simply feel invalidated and close down.

Instead, try these strategies for helpful listening:

- Provide nonverbal reassurance. Holding someone’s hand expresses support without words. Learn to allow for crying and even silence. If you start to feel anxious, calm your body with slow, deep breaths. Gently think about how much you care for this person.

- Encourage them to talk. Let them know they have your full attention. “I’m here to listen. I’m in no rush. Tell me what’s going on.” Or, “Tell me more about that.” As the conversation ends, conclude with something affirming, such as “I’m so glad you shared this with me. It really helps me understand.”

- Practice active listening. Repeat or paraphrase what they have shared. “So, it sounds like you’re afraid this is going to be the end of your independence,” or “From what you’ve said, it sounds like you’re worried this might be a more serious diagnosis.” This helps them feel genuinely “heard.”

- Validate their feelings. Affirming phrases help people feel that they are not alone. It builds trust and a sense of connection. “I’d feel that way too,” or “I understand how you would respond that way.” While you want them to know they are not alone, resist the impulse to tell them of a time when you were sad, as that typically shuts people down.

- Wait for their cue before problem solving. It’s tempting to start “fixing things” as that is the eventual road to resolution. Instead, wait until you hear your loved one saying things like “I hate feeling this way,” or “I wish I knew what to do.” These are signs that they are ready to begin looking for solutions. Rather than giving advice, ask them questions that help them find their own solutions. “Where might you start? What might be a good first step?” If you have a solution you really want to propose, ask if it would be okay for you to share an idea.

"Going home tomorrow?!"

When your loved one is hospitalized, getting word of discharge “soon” can be heartening: Yay! Improvement! And it also can be distressing. Many aspects of care may drop into your hands. Mobility, incontinence, wound care, oxygen…. And you may not have the needed help lined up.

Good news: There are options. Tell the doctor and the hospital discharge planner immediately of your concerns. According to Medicare regulations, they are required to work with whoever is the “family caregiver” to come up with a safe and appropriate plan.

The hospital may pressure you. (They get paid a fixed fee, so the earlier the discharge, the more money they make.) Your relative may pressure you, too. Ask the hospital for the reasoning behind the discharge plan. Stand your ground for a wise decision about timing and aftercare. If this seems daunting, consider the advocacy services of an Aging Life Care Manager.

There is also a formal appeal process for discharge decisions, but timing is crucial.

- Upon admission, your relative should receive an “Important Message from Medicare.” Keep this paper. It lists the agency that handles discharge appeals. If you don’t receive this document, ask for it.

- Also upon admission, ask the case manager (aka, discharge planner) how long your relative will likely be staying and if they are officially “an inpatient” or just there for “observation.” The appeal process is only for patients who have been formally admitted.

- As soon as you have safety concerns about the discharge, alert the doctor and discharge planner.

- If the hospital persists with its discharge timetable, contact the reviewing agency immediately and ask for a “fast appeal.” You can ask for a fast appeal up to the day of discharge.

A review usually takes twenty-four to forty-eight hours. Medicare will continue to pay for your loved one’s hospital stay during the review (although the deductible and usual copays still apply).

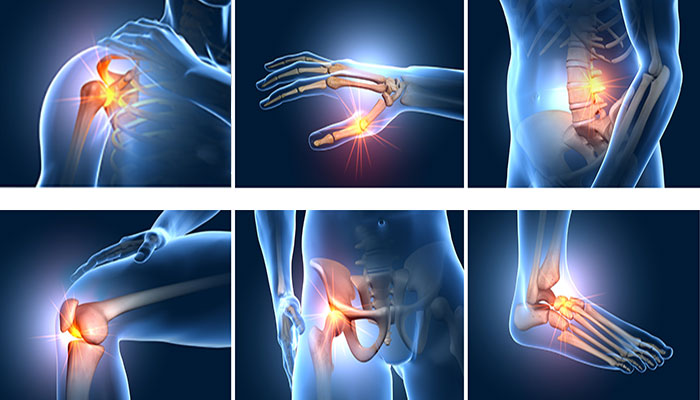

Return to topSigns of chronic inflammation

Chronic inflammation occurs when the immune system doesn’t shut down properly. Instead, it attacks the body. This can last for months, even years. It’s like a persistent internal war. It puts the body under tremendous stress. There is growing evidence that chronic inflammation is involved with a number of problems common in aging. These include heart disease, some cancers, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s. Also, bowel disorders, lung disorders, diabetes, depression, and several autoimmune conditions.

Most people don’t feel the symptoms of chronic inflammation directly. Instead, they discover it’s there when they delve into other health concerns, such as possible arthritis or unexplained weight gain or loss. Addressing chronic inflammation can ease the stress on the body and help slow the development of serious conditions.

Signs and symptoms. Because chronic inflammation can affect many body systems, you might want to talk with the doctor if your loved one is experiencing any of the following. (Yes, it’s a dauntingly broad list! But any combination of symptoms will help the doctor determine next steps):

- Joint or muscle pain and stiffness

- Fatigue and muscle weakness

- Gastrointestinal issues (diarrhea or constipation)

- Unexplained weight gain or loss

- Persistent infections

- Skin rashes

- Dry or gritty eyes

- Balance issues, especially when walking

- Insulin resistance (also known as “prediabetes” or “metabolic syndrome”)

- Depression, anxiety, or other mood disorders

- Brain fog

Getting tested. There is no one test for chronic inflammation. But there are a few blood tests that can indicate the level of generalized inflammation. C-reactive protein, sedimentation rate, and fibrinogen are the most common. Talk with the doctor. They may want to also order other tests to zero in on the particular system that appears to be under attack.

Return to top